By James Caton

Disappointing GDP growth and high inflation have many commentators talking about stagflation. Advanced estimates from the Bureau of Economic Analysis suggest real GDP fell for a second straight quarter in 2022. At the same time, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) reached a forty-year high in June. Falling energy prices left the headline CPI unchanged in July, though core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices and is typically thought to be a more reliable predictor of future inflation, remained high at 5.9 percent year on year.

Are we experiencing a1970s style stagflation? By a measure of the raw inflation rate, the simple answer is “no.” Inflation had hit double digits on multiple, extended occasions during the 1970s. Currently, neither the CPI (9.1 percent in June) nor the GDP deflator (7.5 percent in Q2) has broken into double digits. The most important distinction between inflation in the 1970s and the present inflation, however, is the nature of the monetary regime. Today’s Federal Reserve has already begun taking aggressive action to bring down inflation, and investors seem to believe it will succeed. During the 1970s, the Fed continually increased the quantity of money and did so at an increasing rate. Paul Volcker assumed leadership at the Federal Reserve in 1979. However, inflation expectations were not immediately tamed. Inflation would not fall below 5 percent until the last quarter of 1982. In the same quarter, unemployment peaked at 10.8 percent. The Volcker Fed adopted countercyclical interest rate targeting in an effort to stabilize inflation expectations which had been high and variable at the time.

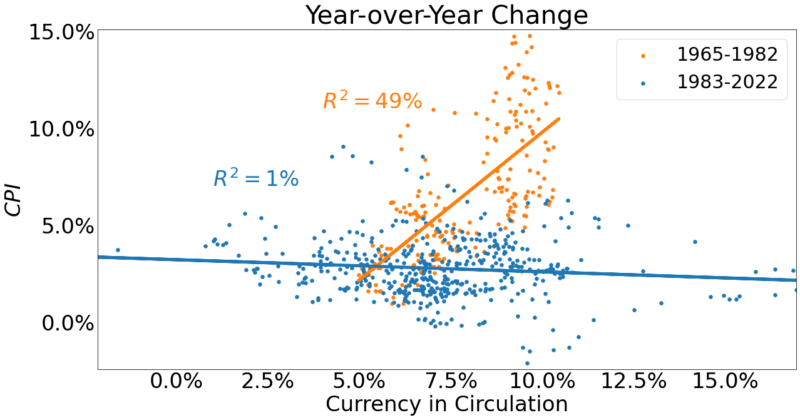

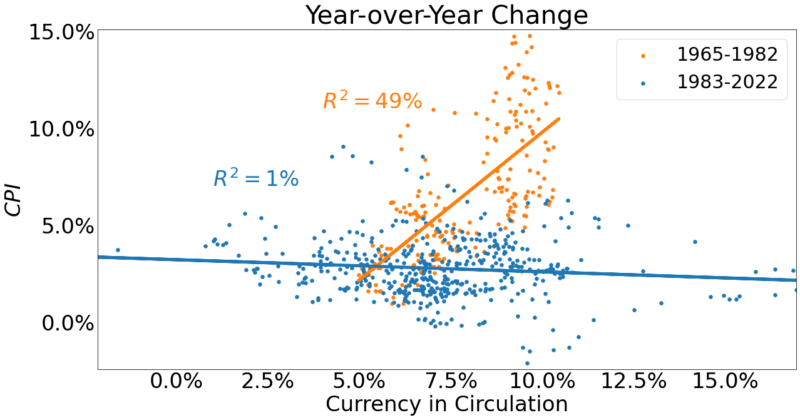

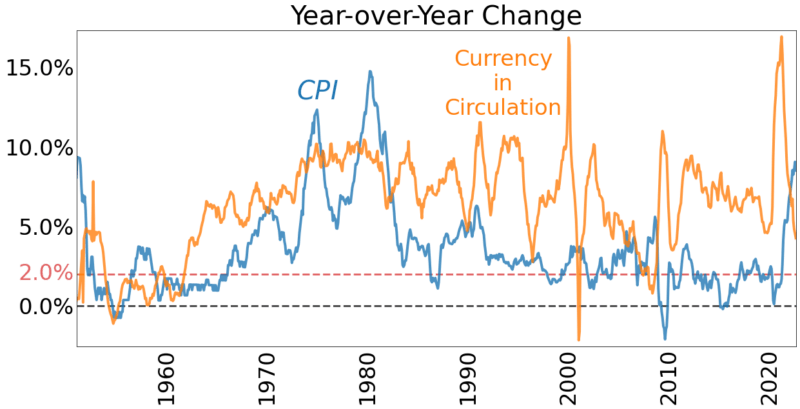

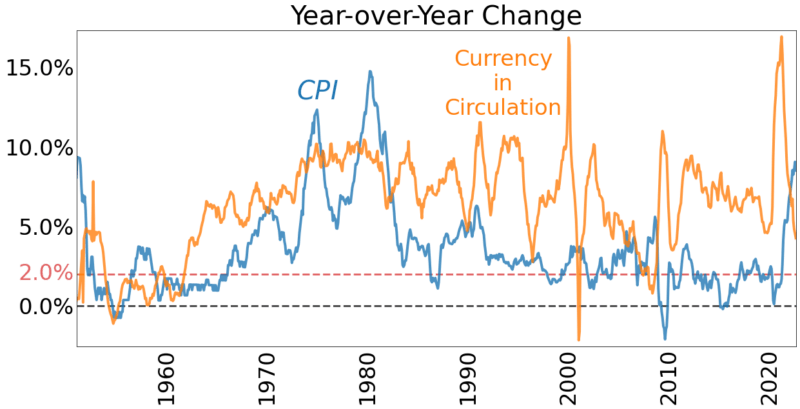

The lack of response of monetary policy to growing inflation makes the 1970s an ideal period for demonstrating the quantity theory of money, which states that the rate of inflation is a function of the rate of expansion of the quantity of money. The rate of monetary expansion chosen by the Federal Reserve from 1965 to 1985 was highly correlated with the rate of inflation. Using only the quantity of currency in circulation, which excludes currency held at the Federal Reserve, I find that nearly half of the variance (R2=0.49) in the rate of inflation during the period can be explained by money growth. The tight correspondence between money growth and inflation between 1965 and 1982 is partly due to the fact that money growth was consistently high: Even if currency expansion impacted inflation with a lag, the persistent upward trajectory in the rate of expansion makes the relationship between inflation and the rate of currency expansion straightforward to tease out. The rate of currency expansion hovered around 10 percent between 1978 and 1980, enough to generate significant inflation despite positive real economic growth.

Once countercyclical monetary policy was adopted and effectively implemented, however, this relationship between the growth rate of currency and inflation broke down. It is not because the quantity theory became invalid. Rather, investors began to expect that monetary policy would tighten as inflation rose above target, and that it would ease as economic conditions threaten to push inflation below target. The FOMC typically promotes change in the interest rate target by inversely adjusting its rate of accumulation of securities. Even if the Federal Reserve significantly increased the rate of expansion of currency for a short period of time, investors were confident that the Federal Reserve would slow expansion enough to lower inflation. Since interest rates tend to reflect inflation expectations, the Fed’s countercyclical expansion and contraction of currency in circulation also tended to stabilize interest rates.

In the late 1970s, the Fed had developed a reputation for allowing persistently high levels of inflation, and there was little in the way of a credible plan for the Fed to reduce the high rate of inflation. The sudden collapse of inflation leading into 1983 was the result, not of an equally large slowdown in the growth of the quantity of money, but rather the first modest slowdown in expansion of currency. This indicated a willingness of the Volcker Fed to follow through on its promise to get inflation under control, but investors would not be immediately convinced. As the Volcker Fed consistently slowed the rate of growth of currency in response to rising inflation, low and stable inflation became the norm. By the early 1990s, inflation expectations became firmly anchored under Alan Greenspan who followed a similar countercyclical program.

Inflation Expectations Today

During the transition to a regime of quantitative easing (QE) under Ben Bernanke, many worried that the massive increase in the Fed’s balance sheet would generate runaway inflation. Many were surprised when inflation struggled to remain at or above the Fed’s 2 percent target. Perhaps this created the illusion that inflation expectations were unshakeable and, perhaps, that significant increases in the rate of expansion of circulating currency would not promote similar increases in the rate of inflation.

The Powell Fed has learned that it was wrong in its assumption about the ability of inflation expectations to remain anchored even in light of a 6 month period where year-over-year expansion of currency in circulation was persistently above 15 percent. “Inflation has obviously surprised to the upside over the past year,” Powell recently noted, “and further surprises could be in store.” Yet, the rate of expansion of currency has slowed to pre-pandemic lows and the Fed has signaled that it is committed to raising the federal fund rate target until monthly inflation readings cool to a rate consistent with the FOMC’s 2 percent target. Falling inflation expectations suggest that investors believe the Powell Fed is credible. Further, since inflation expectations have risen only modestly, there should be little concern about recession deepened by disinflation.

Expectations of inflation and inflation volatility remained high even under Volcker in the early 1980s. The Volcker Fed finally succeeded by reducing the rate of inflation before convincing investors that the Federal Reserve was serious about taming inflation. Unemployment peaked at 10.8 percent in December 1982, and would not fall below 7 percent until 1986!

A likely reason for this persistently high unemployment was that wage demands of employees included adjustment for future inflation comparable to rates in the 1970s and 1980s. Throughout the remainder of the decade, the interest rate on 1 Year U.S. Treasuries remained well above the rate of inflation, often by about 500 basis points. The Federal Reserve had not yet vanquished the fear of an inflationary surprise among investors and among labor.

The current mismatch between inflation expectations and present rates of inflation suggest that inflation expectations are still well-anchored. Indeed, inflation expectations are currently falling ahead of observed inflation and ahead of expected rate hikes. Having prevented the unanchoring of inflation expectations, the Powell Fed is avoiding generating volatility in inflation and interest rates that would otherwise deepen recession. Supporting this view, mortgage rates fell significantly only a day after the 75 basis point increase in the federal funds target.

If we are experiencing “stagflation,” it is certainly not the kind that struck in the 70s and early 80s. Investors have been surprisingly patient in their assessment of future inflation. A falling inflation rate should promote stability without pushing unemployment persistently above the natural rate of unemployment, which is probably in the range of 4 to 5 percent. Further, supply side constraints might slow the fall in the rate of inflation and weigh on real growth as the conflict in Ukraine may further elevate energy prices.

Still, the FOMC has taken action to reduce inflation generated by monetary policy. It has reduced the year-over-year growth of currency in circulation to nearly 4.19 percent, lower than any rate observed since 2010. The FOMC’s current policy stance has precipitated a recession that may modestly deepen as it tardily-but-effectively pursues its commitment to restraining inflation.