Economic growth is slowing in China, and people are worried. The regime’s backward rush to Maoism has intensified the pessimistic mood. While frenetic business activity has returned to post-COVID Beijing, problems are evident. For instance, from my hotel window I spied a half-finished skyscraper on which construction had halted, evidence of the country’s deep real estate slump.

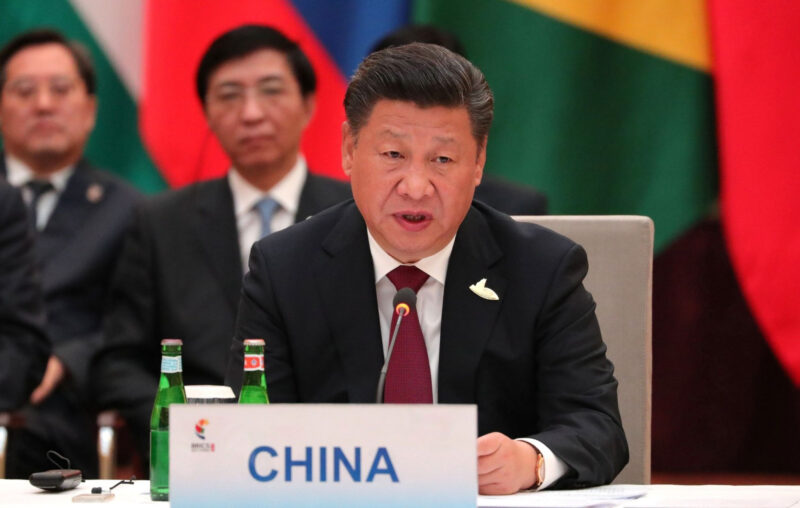

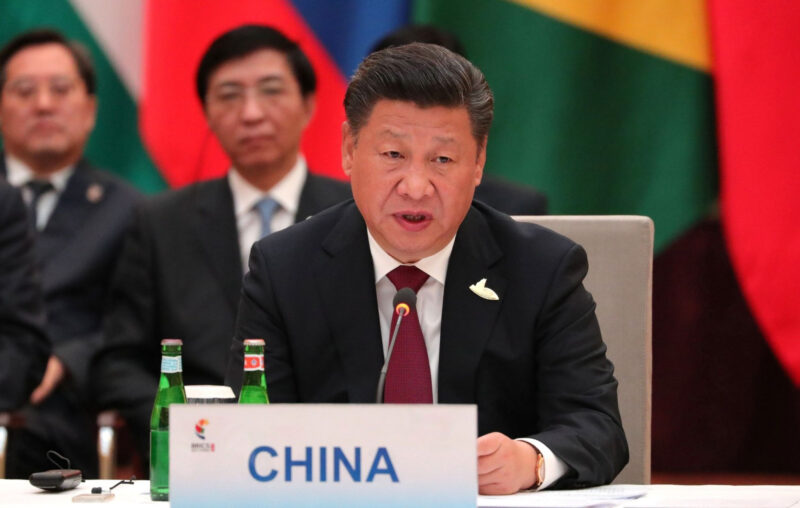

To help spur the economy, President Xi Jinping addressed investors at November’s APEC summit in San Francisco, promising to create a “world-class business environment.” Government policy, he explained, was “designed to make it easier for foreign companies to invest and operate in China.” Xi’s pitch was tacit acknowledgement of his own failure.

Mao Zedong, the mad “Red Emperor,” proclaimed the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949. Millions of Chinese died during the Chinese Communist Party’s brutal consolidation of power, vicious Anti-Rightest Movement, disastrous Great Leap Forward, and deranged Cultural Revolution. Amid the violence and chaos Mao constructed a strict socialist society, ensuring widespread immiseration.

Only Mao’s death in 1976 brought relief. China’s subsequent liberalization demonstrated the power of private enterprise and free markets. “Paramount leader” Deng Xiaoping’s modest deregulation yielded tremendous growth by loosing the entrepreneurship of hundreds of millions of people. For years the PRC’s economy expanded explosively. The poverty rate dropped dramatically. Although CCP officials took credit for China’s growth, the critical factor was reversing their earlier collectivist nostrums, which treated the Chinese people as veritable human automatons.

A dozen years ago, the colorless apparatchik Xi Jinping, who had carefully ascended the PRC’s political hierarchy, took control, becoming both CCP general secretary and Chinese president. There was much hope that he would be a reformer, clearing away state economic controls and encouraging international trade.

He proved, however, to be Mikhail Gorbachev in reverse, disguising his true intentions to recommunize the economy and rest of society. In fact, the nature of his rule was presaged during the final days of his vice presidency, when he disappeared from public view, apparently busy combating an insurgent reach for power by the charismatic Bo Xilai, a provincial governor. Having elevated Xi with the responsibility to strengthen party unity in a crisis, CCP paladins should not have been surprised when he accelerated his campaign after being installed.

He has entered his third term, by all likelihood chairman and president for life. He is oft said to be the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao. In fact, he has become another Mao, acquiring virtually untrammeled power, filling the Politburo with his hirelings, and making the CCP the center of not just Chinese politics, but communal life.

Although the PRC before him was not free, it was notably freer. It was a loose authoritarian system in which both public disagreement and private dissent were tolerated. Even dilute criticism was possible, involving independent journalists, human rights lawyers, non-governmental organizations, and more. Contact and cooperation with Western academics, thinkers, and activists was easy, common, and accepted.

Xi seems to have made his primary objective returning to the Bad Ole’ Maoist Days. His principal objectives have been strengthening both party and personal control. He has exhibited Joseph Stalin’s skill in eliminating all visible party opposition and establishing a burgeoning personality cult, with “Xi Jinping Thought” now part of the constitution. To convince the Chinese people to behave as he demands, the CCP has rewritten history, punishing those who embrace reality.

The government explicitly warns against “Western values” and more closely scrutinizes invitations to foreigners. Overall, “[u]niversities and research centers, including many with global ambitions, are increasingly cut off from their international counterparts.” Online criticism is not just quickly removed but its authors are threatened and punished. Discordant public voices have essentially disappeared. Loose provincial regulation of religion has given way to brutal national controls. Overall, detailed Ian Johnson of the Council on Foreign Relations: “China’s small but once flourishing communities of independent writers, thinkers, artists, and critics have been driven completely underground, much like their twentieth-century Soviet counterparts.”

The PRC’s return to political totalitarianism has weakened the economy. Beijing already faced strong headwinds. Although companies are not pulling out in great numbers, surveys reveal that firms around the world are less willing to invest in China. Last year foreign investment turned negative. Bloomberg reported “less willingness by foreign companies to re-invest profits made in China in the country.” Moreover, Chinese outflows exceeded foreign inflows in 2023 for the first time in five years.

Why the negative results? Western firms complained of “tepid economic activity, unpredictable regulation, worries over employee safety and curbs on transferring data overseas.” But, Johnson observed, “these economic problems are part of a broader process of political ossification and ideological hardening.” Business executives recently complained that Xi’s government “has restricted access to data and sparked raids and investigations involving foreign firms assessing investment risks in the country.”

Alas, this was inevitable. Xi expects business as well as people to serve the CCP. As authoritarian controls metastasize throughout the economy, everyone suffers. For instance, even foreign enterprises now must accommodate party cells. The Wall Street Journal’s Lingling Wei reported on a Chinese “official, one of several who had helped introduce Western-style stock trading to China,” who cited “a worrisome trend of the party inserting itself more into companies’ affairs by pressuring them to accept Communist Party committees in their offices. ‘The whole thing about getting listed companies to set up party committees,’ he said, ‘is a reversal of what we had tried to do’.”

A couple years ago, Beijing silenced critical market analysts. Now the regime jails them. In early January the Ministry of State Security arrested the head of a foreign consultancy for allegedly spying for the United Kingdom. Reported the South China Morning Post: “the Chinese leadership is intensifying a crackdown on stealing secrets, with a major amendment to its anti-espionage law that took effect in July. Consultancy firms are in the cross hairs over the information they obtain.” Deploying the secrecy enactment, MSS declared war on private business. Among the ministry’s recent activities were “raids on Chinese offices of US due-diligence firms and questioning of staff at the Bain consulting firm.”

The PRC’s media has explicitly targeted Western firms: “China’s state broadcaster accused Western countries of trying to steal sensitive information in key industries with the help of consulting firms that help investors navigate the murky Chinese economy.” Geopolitical tensions have made “western business people worry that police may be looking for excuses, whether security-related otherwise, to flex muscle.”

Xi’s focus has become increasingly paranoid and insular. What for the West are good investment practices are, for the PRC, increasingly serious crimes. The CCP believes that economic research, “often involving interactions with Chinese nationals, has exposed state secrets, threatened the party’s control over how the rest of the world views China and helped the US and its allies develop a hardline policy toward Beijing.” Indeed, the MSS now targets this area. Reported Nikkei Asia: “A [ministry blog] post in November focused on finance, claiming that people seeking to ‘profit from turmoil’ are trying to ‘shake investment confidence and cause financial instability in the country.’ The ministry appeared to indicate that it considers stoking financial anxiety, then short-selling stocks to profit from it, to fall under its remit.”

Nor is this all. Forming an opinion, at least a negative one, about China’s economy is another crime. So is releasing critical economic assessments. Even if you aren’t arrested for discovering the truth, you can’t repeat it. Explained the ministry: “False theories about ‘China’s deterioration’ are being circulated to attack China’s unique socialist system.”

Political activists often accept the risk of arrest for their cause. Businessmen, not so much. At the very time economic conditions are deteriorating in the PRC, foreign investors are less able to accurately assess markets. Some expatriates express the desire to return home. The Wall Street Journal found: “Some Western firms have paused research work in China, especially when related to technology and other sensitive areas, according to business executives. Analysts at Wall Street firms, including those specializing in recommendations of Chinese stocks, said they are worried about getting their contacts in China in trouble because of the heightened government scrutiny over foreign connections.”

No wonder foreign investors have soured on the PRC and are pulling their funds.

Xi wants to keep foreign funds flowing into China. For investors, however, expanding CCP controls belies Xi’s reassuring rhetoric. A society with totalitarian political and social controls can’t allow a market to be truly free. Liberty ultimately is indivisible. And tyranny doesn’t pay.